P-Prompt: Never yours to begin with

The Collective Conditions for reuse start with a stark reminder that none of us ever arrives first at the scene, even if in the context of capitalism, we might feel forced to believe or pretend that we do:

“REMINDER TO CURRENT AND FUTURE AUTHORS: The authored work released under the CC4r was never yours to begin with. The CC4r considers authorship to be part of a collective cultural effort and rejects authorship as ownership derived from individual genius. This means to recognize that it is situated in social and historical conditions and that there may be reasons to refrain from release and re-use.”

Three years ago, in the margins of another conversation, Marloes de Valk wondered about who is being addressed in this preamble, and what to make of its commanding tone. At the time, a friend alerted us to Marloes' discomfort, but we somehow never found the time to speak about it in person. For Revisit Reuse we asked her to come back to that almost forgotten moment and to articulate what she meant in the shape of a prompt. "I wondered how intersectional, feminist, anticolonial work could start with such a universal claim of disappropriation", she wrote.

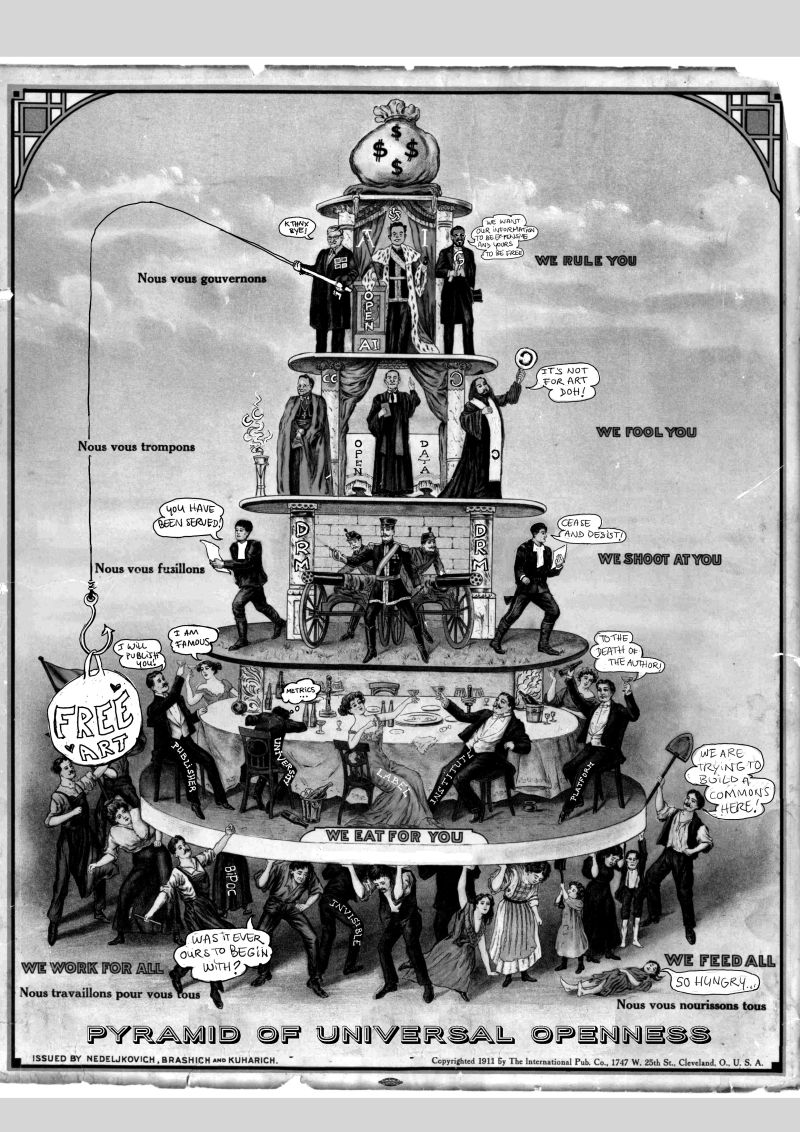

In a letter and an image collage based on a 19th century cartoon The Pyramid of Capitalist System, Marloes proposes us to differentiate between those at the top of the “Pyramid of Universal Openness” and those at the bottom, pushing back at the blanket dismissal of authorial ownership that both CC4r and CC4r-r attempt. She argues that such a dismissal risks to mainly empower the (re)user, "who gains unrestricted free access to culture, but weakens the position of the [precarious] creator who is often at the mercy of intermediaries such as publishers, producers or institutions."

"Even in precarious conditions, we create meaning in conversation, we write to our friends. Universal dismissal of ownership and authorship risks creating the same ‘terra nullius’ as universal openness does. How can we grow stronger together while surviving within late capitalist economies?"

Dear CC4r (re)writers,

I’m sad I cannot come to Brussels to think about a renewed CC4r with you, but what a privilege to be invited to write a prompt that might support this work! Before I formulate my prompt, which took the form of three questions, I will try to describe my initial confusion about the CC4r preamble and I will try to visualize it so you can hopefully see what I mean (see “Pyramid of Universal Openness”).

When I first read the preamble’s first sentence; “The authored work released under the CC4r was never yours to begin with”; I thought it addressed me as a writer. I thought it told me that if I used this license, it means I accept that the labor I invested into the creation of the licensed work, and the outcome of that labor, were never mine to begin with. I wondered how intersectional, feminist, anticolonial work could start with such a universal claim of disappropriation.

When I read on, I realized the license wasn’t meant to deny me my work; not the labor nor the outcome of it. On the contrary, it tries to challenge universalist approaches to openness that have led to unjust appropriation and invisibilisation. It tries to challenge the colonial power structures at play in the circulation of creative work that have damaged, and are damaging, creators who are part of marginalized groups. Rather than invisibilising authors, it calls for generous citational practices acknowledging that creative work is never done in isolation; citational practices such as discussed by Kathrine McKittrick in Dear Science and Other Stories (2022). I wonder if the difference between acknowledging creation is done collectively, and ownership of one’s work as a means to earn a living, could be made clearer?

This need to (even if reluctantly) attach your name to something you worked on while fully acknowledging the many others that helped you create it, the others you are creating it with and the acceptance of the otherness of the ones you write to, is beautifully expressed by Kathy Acker in Writing, Identity, and Copyright in the Net Age (1995), a text Femke recommended me. Even in precarious conditions, we create meaning in conversation, we write to our friends. Universal dismissal of ownership and authorship risks creating the same ‘terra nullius’ as universal openness does. How can we grow stronger together while surviving within late capitalist economies?

After my initial confusion, I thought perhaps “never yours to begin with” wasn’t addressing the creator(s) but the person wanting to (re)use the licensed work. The license centers re-use, which centers the user rather than the creator, something Séverine Dusollier discusses in the context of Creative Commons licenses in The Master’s Tools v. The Master’s House: Creative Commons v. Copyright (2006). She argues that Creative Commons has developed a rhetoric convincing artists to share their work for free. This empowers the user, who gains unrestricted free access to culture, but weakens the position of the creator who is often at the mercy of intermediaries such as publishers, producers or institutions. Could the license center the creator(s)?

I find the CC4r a very inspiring text, especially because it is an invitation for situated reflection on ownership, collective authorship, (mis)appropriation and citational practices, rather than a universal commandment to decline the right to authorship, which risks perpetuating the moral imperative propagated by Creative Commons that the CC4r license tries to undo.

For these reasons, I would like to invite you to think about a preamble that is commanding only to those at the top of the “Pyramid of Universal Openness”. I’d like to ask you three questions that might help do this:

★ Could it be made more clear who the license addresses, the creator(s) of a work or those wanting to (re)use it?

★ Could it be written in the voice of the (collective of) artist(s) and writer(s), rather than that of the (re)user and culture industry?

★ Could it empower the creator(s) by emphasizing their right and choice to own their work as the result of their labor and as that on which their livelihood depends while encouraging generous citational practices?

Thank you so much for reading and I wish you a wonderful conversation!

Marloes

References

Kathy Acker (1995). Writing, Identity, and Copyright in the Net Age. The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, Vol. 28, No. 1, Identities (Spring, 1995), pp. 93-98.

Séverine Dusollier (2006). The Master’s Tools v. The Master’s House: Creative Commons v. Copyright. Columbia Journal of Law & Arts, 2006, vol. 29, p.271-293.

Katherine McKittrick (2022). Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.